What Every School Leader Needs to Know

Know

About English Learners

By Sonia Soltero, Karen Garibay-Mulattieri, and Rebecca Vonderlack-NavarroWhile a “majority-minority” student population has long been a reality in the City of Chicago, 2011 marked the first time that minority students were the majority in kindergarten through third grade classrooms across Illinois, according to a Latino Policy Forum analysis of 2010 U.S. Census Bureau data (see below).

Within this demographic shift, the majority of students come from immigrant families who are typically unfamiliar with how to navigate the school system in the United States. They also have a range of levels of proficiency in English and varied levels of academic native language. The term “English Learner” has been used since No Child Left Behind to describe students who need specialized instruction to master the academic English necessary for scholastic success. Illinois is currently referring to English Learners as “Emergent Bilinguals,” to focus on their potential to become fully multilingual. These students’ educational experiences and academic opportunities serve as a critical conduit for how they will flourish and succeed as adults. The preparedness of educators to build on students’ linguistic and cultural strengths has a major impact on the future of Illinois.

Emergent bilinguals (formerly referred to here as English Learners or ELs) are students designated as needing support in learning English as their new language. Emergent bilinguals reside throughout Illinois, with significant growth in suburban and rural areas. They reside in 92 of 102 Illinois counties with 74 of those counties doubling their population between 2005 and 2017. Within that same period, 31 Illinois counties experienced a new presence of emergent bilinguals, according to research by the Social Impact Research Center of the Heartland Alliance.

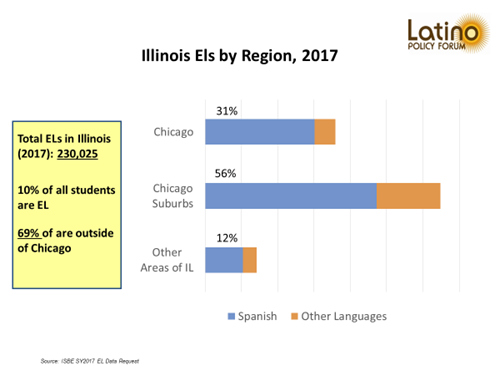

The greatest concentrations are in the City of Chicago (31%); 56% in the Chicago metropolitan areas, and 12% downstate (See chart by region). While the overall growth of emergent bilinguals statewide was 47%, there was a 6% growth in the City of Chicago and a striking 78% growth rate in the suburban areas. Despite the growth across the state, general education teachers are not required to have any training on how to educate these students who are learning English as their new language while also learning academic content.

Longstanding myths about how emergent bilinguals learn and develop language proficiency in English have negatively impacted generations of students. Drawing from Sonia Soltero’s Schoolwide Approaches to Educating ELLs: Creating Linguistically and Culturally Responsive K-12 Schools, we summarize common misconceptions about educating these students. Each myth is counter-argued based on extensive research in the field of second language acquisition and bilingualism. Understanding these facts provides the necessary starting point to have informed discussions for crafting a shared vision to serve emergent bilinguals. This knowledge should drive the implementation of appropriate curricular, instructional and assessment practices. Read a district example of emergent bilinguals highlighting their academic success and provides guiding questions for educators and educational leaders.

Facts Regarding Second Language Acquisition

Acquiring a second language is not a straightforward undertaking. Many factors influence not only how long it takes to become proficient, but also the level of sophistication in the second language. Factors that influence second language acquisition that are internal to the learner include personality traits, age, motivation, attitude, self-esteem, learning style, and level of proficiency in the native language. External factors involve structural conditions typically outside the control of the learner. The quality of second language instruction, access to speakers of the second language, teacher expectations, education policies and instructional practice, and society’s attitudes toward the learners’ backgrounds affect students.

How Long Does It Take?

Acquisition of academic second language takes between four to nine years compared to one-to-two years to develop social second language. Why the difference? Social language is acquired faster because it is supported by context. It is less dependent on prior knowledge, has fewer complex language structures, and is made up of simple everyday words. Social language is driven by greater interpersonal motivation. Academic second language, on the other hand, has less context, more complex sentences, and is more abstract. It contains low frequency and content-based vocabulary. Educators must consider that even native English speakers do not come to school with fully, or even partially, developed academic English. For emergent bilinguals, the difficulty in learning academic language in addition to learning content in a language they do not fully understand is significantly amplified.

What Are Some Common Misconceptions?

Misconceptions about learning a second language perpetuate myths about bilingual education and emergent bilinguals. This includes the notion that children will be confused by being raised with two languages; that the first language is a crutch and should not be used; that younger children acquire the second language more easily and quickly than older students; and that parents should not speak to their children in the first language. These “myths” have been refuted by decades of research in the United States and abroad, including Crawford’s Ten Common Fallacies about Bilingual Education; Espinosa’s Challenging Common Myths about Dual Language Learners; McLaughlin’ Myths and Misconceptions about Second Language Learning; and Soltero’s School-wide Approaches to Educating ELLs.

Fact: Emergent Bilinguals Need Specialized Support

General educators, school leaders, and even parents are not always aware that providing specialized services for emergent bilinguals is required by federal and state law. It is a necessary support for them to develop English and achieve academically. Emergent bilinguals are expected to learn English and the academic content at the same pace and level as their native-English-speaking peers, who do not have the added burden of learning a second language. While their English-speaking peers are learning academic content and progressing in literacy acquisition, emergent bilinguals fall behind if they do not receive specialized second language instruction through specially designed materials and instructional methods. In addition, students who are in classrooms where the native language is used for instruction are better served linguistically, culturally, socially, and academically.

Fact: More English is Not Better

The time-on-task hypothesis maintains that emergent bilinguals must be exposed to great amounts of English to become proficient in the language and also that instruction in the native language interferes with the acquisition of English. Research evidence, including “Bilingual Education in the 21st Century, A Global Perspective,” rejects this claim and instead suggests that students who receive instruction in the native language develop English more efficiently than children who are immersed in the second language. Context factors, such as development in the first language, parent support, and status of each language, are much stronger determinants in the outcome of initial first or second language instruction.

Fact: Immigrants Want to Learn English

Contrary to popular belief, the strong need to learn English and the loss of the native language is increasing among immigrant groups. They now shift to the majority language by the second generation. A few decades ago this used to happen in the third generation. The loss of the native language and culture is often seen as necessary to develop and achieve academically in English. But when emergent bilinguals lose their first language, not only do they experience loss of personal identity and emotional bond with their communities, but also often experience rejection from U.S. society.

Access to adult language classes is a major problem for those who want to become proficient in English. The demand for adult ESL classes is increasing as their funding and availability decrease. In addition to the shortage of ESL instruction, other obstacles to learning English reflect the inequality that results from poverty, including extended and/or non-traditional work hours, transportation, and childcare.

Fact: Speaking English Is Not Proof of English Proficiency

A pervasive misconception is that once emergent bilinguals are able to speak in English, they are proficient in it and are able to function in the classrooms at the same level as their native-English peers. Research again disputes this notion. Some emergent bilinguals who have no accent and are able to use English for everyday social interactions on familiar topics may appear to be fully proficient. They may not necessarily have yet developed the decontextualized and cognitively demanding language needed for thinking, speaking, and writing about academic subjects (Cognitive Academic Language Proficiency, or CALP). Misconceptions about second language proficiency often lead educators to exit emergent bilinguals too early into general education classes based on their English conversational skills (Basic Interpersonal Communicative Skill—BICS) alone. These reclassified “former” emergent bilinguals no longer receive specialized academic or language support in the form of ESL or bilingual services even though they continue to struggle with the demands of academic English.

Strategies to Consider

Strategies to ConsiderThese types of misconceptions about emergent bilinguals are pervasive and affect decision-making at all levels: classroom, school, district, and state. Programs and services for emergent bilinguals must be grounded on the standing theories and research in the field. A necessary starting point is to become knowledgeable about the complexities of acquiring a second language, the socio-emotional aspects of navigating a new culture, and how the socio-political environment affect emergent bilinguals and their families.

Therefore, it is critical that district and school leaders, school board members, teachers, support staff, and the community at large understand the facts about emergent bilinguals. For some school districts in Illinois, organizing presentations and panel discussions that include school leaders, teachers, and former emergent bilinguals and their parents have been particularly beneficial. Other school districts have ongoing book study groups to better understand the various aspects of emergent bilingual education. Others have devoted time and funds to create strategic plans for providing quality educational opportunities and programming for emergent bilinguals. It is also important to consider external and community resources available to emergent bilinguals and their families, such as social agencies and governmental centers with translated informational materials, community social services or clinics with bilingual staff. School districts should have a system to connect parents and families with these types of service organizations to form networks of support.

Sonia W. Soltero, Ph.D., is Professor and Chair of the Department of Leadership, Language, and Curriculum and former Director of the Bilingual-Bicultural Education Graduate Program at DePaul University in Chicago. Karen Garibay-Mulattieri is Senior Education Policy Analyst at the Latino Policy Forum in Chicago. Rebecca Vonderlack-Navarro, Ph.D., is Manager of Education Policy and Research, also at the Latino Policy Forum in Chicago. Resources for this article can be accessed at http://bit.ly/ND19Jres.

Illinois English Learner Handbook for School Leaders

This Journal entry is part of a comprehensive Handbook designed to assist local communities in understanding the unique needs of emergent bilinguals and how research-based best practice can inform the creation of a local vision that is equitable and supports all students. The Handbook, due to be published in early 2020, is a collaborative effort between the Latino Policy Forum, Illinois Association of School Boards, Illinois Principals Association, and Illinois Association of School Administrators.

The Handbook will be comprehensive and tailored for multiple audiences. One section is aimed at school board members and lawmakers charged with drafting policy and appropriating resources who may wish to develop their background knowledge on emergent bilinguals. The Handbook will offer district administrators, emergent bilinguals directors, and school leaders a detailed overview for how a vision might be implemented, funded, and monitored. Many sections, including the one published here featuring Berwyn North SD 98, include a district highlight.

There are no silver bullets in education, but the research tells us that, on balance, the recommendations and guidelines to be presented in the Handbook provide the best practices for making a significant difference for emergent bilinguals educational outcomes.