Discipline Equity Audits: Courageous Conversations and a Plan for the Future

By Trevor Chapman and Beth Hatt

How can schools address inequities in student discipline? Given the increase in racial tensions across our nation, it goes without question that schools are working diligently to find ways to identify and resolve inequities.

Not all schools break down their discipline data by student subgroups such as race, free and reduced lunch, or special education designation. However, once they do, many school personnel are surprised to see inequities within the data they did not know existed. Schools’ over-representation of student discipline for student subgroups is challenging to talk about because it elicits emotions from students, teachers, administration, and families. Nonetheless, it is one of the essential pieces of data for both central office administration and building leadership alike to examine and consider ways to move towards more equitable practices.

Specifically, Black students, LatinX students, Native American students, students receiving special education services, and students qualifying for free and reduced lunch receive discipline more often than other students.

Given that all educators share a common goal of ensuring that every student can succeed, schools need to pay attention to school discipline inequities. By looking at and resolving over-representation in office referral and school suspension data, research demonstrates school districts will simultaneously improve academic achievement and increase graduation rates by keeping students in school and engaged.

What is the first step to address inequities in student discipline? The best answer to this question is not straightforward. Instead, it is a winding road of data collection and interpretation, coupled with courageous conversations about the next steps. How might data be collected, and who should examine it? What issues may exist, and how do we address them? These are questions every district should be asking to uphold ideals of fairness and equal opportunity.

It is a hidden problem because it gets perpetuated largely through implicit bias and systemic issues — despite administrators’ and teachers’ best intentions. One of the authors of this piece, Trevor Chapman, a high school principal, facilitated a discipline equity audit process. We hope that, by sharing the process and lessons learned, it will encourage other school and district leaders to engage in courageous conversations necessary to reduce over-representation in discipline data.

Historical Context and Cycle of Discipline

Research literature suggests that student suspension is often used in schools to decrease inappropriate behavior as a form of discipline. However, no research evidence exists to support suspending students as a useful tool for improving student behavior. Instead, research indicates that suspending students creates a climate of distrust between students and school staff and produces an environment in which students are less successful because they are not attending classes while suspended. Low achievement and discipline inequities are closely tied because when students are referred to the office regularly or suspended, they often lose instructional time and fall behind. Furthermore, data suggests students of color, students in special education, and students who receive free and reduced lunch are more likely to be over-represented in discipline data. The disparities among students regarding school discipline are apparent across multiple studies over many years, specifically since the early 1970s. The U.S. Department of Education Office for Civil Rights collected data (Civil Rights Data Collection, CRDC) as part of a brief regarding school discipline across the United States. Most notably, the CRDC 2014) showed that Black students and students with disabilities are disciplined at far higher rates than their peers, beginning in preschool. According to the CRDC (2014), Black students are suspended and expelled at a rate three times greater than white students. This same document showed that, on average, 5% of white students are suspended, compared to 16% of Black students, with Black girls having the highest rate of suspension. In districts with less racial diversity, the impact typically falls on low-income students and students with disabilities.

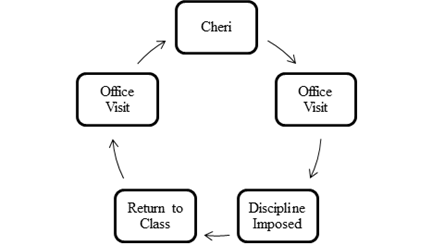

Consider the visual representation below, based on a student whom we will name Cheri, which depicts the cycle of school discipline. As educators, we can stop the process from continuing. Many students begin their days in classes. For some, there may be a behavioral infraction that occurs, resulting in that student being sent to the office. Once the student is in the office, an administrator implements a routine disciplinary measure and consequence. After completing the consequence, the student returns to class. He or she may reenter after serving detention, or perhaps after missing multiple days for a suspension. However, in the majority of cases, the student goes directly back to class. Unfortunately, many students circle back to the office for a consequence once again within a short period.

Consider the visual representation below, based on a student whom we will name Cheri, which depicts the cycle of school discipline. As educators, we can stop the process from continuing. Many students begin their days in classes. For some, there may be a behavioral infraction that occurs, resulting in that student being sent to the office. Once the student is in the office, an administrator implements a routine disciplinary measure and consequence. After completing the consequence, the student returns to class. He or she may reenter after serving detention, or perhaps after missing multiple days for a suspension. However, in the majority of cases, the student goes directly back to class. Unfortunately, many students circle back to the office for a consequence once again within a short period.

— Megan Tschannen-Moran

Equity Audit

When district- and building-level leadership are considering a method to address potential inequities, an equity audit may be an excellent resource. Equity audits assist leaders in identifying any issues that may exist in discipline data collected over a period of time. Discipline Equity Audits provide an opportunity for school leaders to disaggregate data by demographics such as race, special education, free/reduced lunch status, language, and gender. Pamela Hoff and Beth Hatt from Illinois State University provide an easy-to-use method to organize district or school discipline data (see resources link for more info).

Form a Team and Lay the Groundwork

Literature supports the use of a team approach when dissecting the data collected using an equity audit. Be advised that starting with a small group of stakeholders may be more manageable, especially if the educational leader is new in facilitating such a group. The author facilitated a group he called an Equity Leadership Team, which included: Principal, assistant principal, two teachers, a behavior interventionist (or other student support person), two parents, and a school resource officer. The facilitator purposefully created and cultivated a group of racially diverse stakeholders who have a vested interest in ensuring equitable discipline practices in our school or district. Being purposeful in selecting these individuals is critical as one works to cultivate this group into a decision-making body for a school or district. The group we formed proved to be very successful in being thoughtful, collaborative, and learned from each other.

“Equity Audits: A Practical Leadership Tool for Developing Equitable and Excellent Schools,” recommends the following steps as part of the decision-making process for completing an equity audit:

-

Create a committee of relevant stakeholders

-

Present the data to the committee and have everyone graph the data

-

Discuss the meaning of the data, possible use of experts, led by a facilitato

-

Discuss potential solutions, possible service of experts, led by a facilitator

-

Implement solution(s

-

Monitor and evaluate results

-

Celebrate if successful; if not successful, return to step 3 and repeat

Once a team is selected, carefully consider a text that can provide the groundwork and common vocabulary needed for this equity team to flourish. It is essential to frame the group’s work through an equity lens, and understanding equity in your school context is a necessary framework to consider. This group relied on the following two texts before beginning the data analysis process: Excellence Through Equity by Alan Blankstein and Pedro Noguera and Courageous Conversations about Race by Glenn Singleton and Curtis Linton. These texts provide the foundation needed for stakeholders to tackle potential equity issues in districts or schools. A book study using such texts would be a recommended starting point for the group. In particular, group members should share their understanding and blind spots related to race, low income, special education, or gender as it pertains to the data. The use of these texts can assist in the beginning and in guiding these conversations.

The Real Work

In examining the data from the equity audit, consider providing small pieces of data to the participants to digest the information as they receive it. A leader in this work would want to allow time for adequate reflection and critical analysis of the data itself. Focus group discussion on questions such as these:

-

What is occurring in our building concerning this data?

-

What is the root cause of these issues?

-

What strategies have already been used by teachers to become more equitable in their teaching practices?

-

What strategies have already been used by administrators to become more equitable in their administrative and discipline practices?

-

What patterns do you notice in this data?

-

What resources do we already have at our disposal in our school community to address issues of equity?

-

Could an outside facilitator assist us in moving through this work? If so, how?

-

Is there an outside expert or research literature that we want to bring into this process to strategize solutions

-

What plan does this committee have moving forward, and how should we communicate this plan

- Consider emerging themes that come organically from the conversations. These themes may become focal points for future professional development for staff. Be intentional about creating an environment to meet with stakeholders that foster organic discussions. Such an environment must provide for space where it is acceptable to disagree and to engage in discourse to examine root causes related to the equity audit results.

Recommendations

As a group of adult stakeholders begins the journey of utilizing an equity audit, consider including student voice(s). For example, involving a student representative from multiple student groups coming to a meeting and sharing lived experiences or facilitating a separate student group that looks at the equity audit results. Consider gathering student voices from students in the over-represented groups found in the data is especially important.

One may also consider reporting progress from your equity leadership team to different stakeholder groups in your school or district. Parents at a PTO meeting would likely appreciate the work you are doing. Staff would benefit from knowing about the equity work of their colleagues. Students participating in student council may appreciate knowing that adults in their schools are working to create an equitable environment for all students. Lastly, as a building level leader, consider sharing results with district-level administration and school boards. These are the decision-makers and policymakers who can use equity audit results in their leadership decisions.