What Board Members Need to Know About The New Standard for Student Proficiency

By John Gatta, Ph.D.

As a component to school accountability systems, federal law requires that each state adopt challenging academic content standards in English Language Arts (ELA), mathematics, and science by grade level. These standards define what students should know and be able to do, and are measured via state-wide assessments. In Illinois, these assessments are the Illinois Assessment of Readiness (IAR) and the ACT.

States further define the construct of student proficiency through proficiency benchmarks, which act as “cut scores” on the state assessments. A student is deemed proficient if they meet or exceed the cut score on the relevant state assessment. Illinois includes the percentage of students who are proficient as a component of its school accountability system.

Student Proficiency is a Policy Construct

It is important to recognize that student proficiency is a policy construct that is separate from the notion of being at grade level. Proficiency compares a student’s academic achievement to a fixed aspirational policy standard, while the notion of being at grade level is a normative construct that compares a student’s academic achievement to what is typical across the state or nation at a particular grade level.

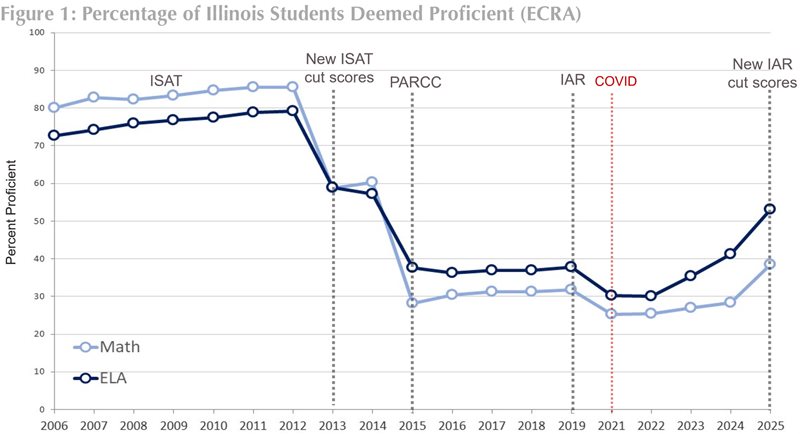

To illustrate, Figure 1 shows a 20-year history of student proficiency in Illinois. It shows the percentage of students proficient in Grades 3 through 8 in ELA and math, with annotations to show changes to state policy.

One can clearly see how changes to state policy affect student proficiency rates. In 2013 and again in 2015, Illinois increased the cut scores for proficiency, and hence Illinois stu-dents showed a sharp drop in student proficiency. This is analogous to the high jump in a track and field meet.

As the high jump bar is raised, fewer athletes are able to clear the bar. The same is true with proficiency. As the standard for student proficiency is increased, fewer students across the state will meet the standard. On August 13, 2025, the Illinois State Board of Education (ISBE) lowered the cut scores for student proficiency, and consequently, student proficiency in 2025 saw a sharp increase.

The key insight is that student proficiency is a measure of student achievement through the lens of state policy at the time assessments were administered. For example, student proficiency in math dropped from roughly 85% in 2012 to less than 30% in 2015, a 55% drop despite there being no measurable difference in the percentage of students at grade level over the same period, as measured through national percentiles.

While state proficiency metrics are meaningful, they lack proper context with respect to actual student performance across Illinois and the nation. Without the proper state or national context, the new proficiency benchmarks are likely to be misinterpreted. This is analogous to pediatric growth charts. To know your toddler’s actual height and weight is meaningful, but as a parent, it is more meaningful to also know what is considered normal via national percentiles.

Issues with the New 2025 Proficiency Benchmarks

Illinois School Report Cards for 2025 reflect a new standard for student proficiency. The Illinois State Board of Education (ISBE) created new student proficiency benchmarks to provide educators, families, and communities with more meaningful data about student success. While the new benchmarks are a step in the right direction toward more mean-ingful performance levels, variation in benchmark rigor across grades and subjects presents interpretation and communication challenges. Without proper context, student proficiency under the new benchmarks is likely to be misinterpreted.

As illustrated in Figure 1, the rigor of proficiency benchmarks has changed over time, leading to large differences in state report card proficiency rates that are unrelated to underlying student achievement. The same is true across grades and subjects.

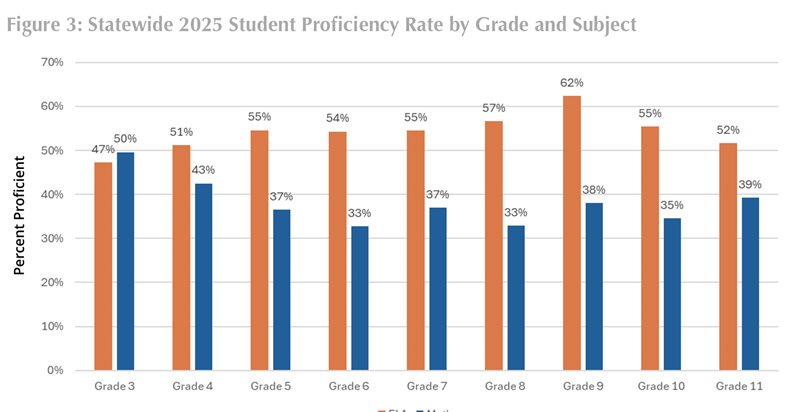

Based on ECRA’s research of more than 1 million students across Illinois who took state assessments, it is much easier to be proficient in some grades and subjects than others. The variation in percent proficient by grade and subject is primarily attributed to differences in competitiveness of the proficiency benchmarks across grades and subjects as measured by national percentiles.

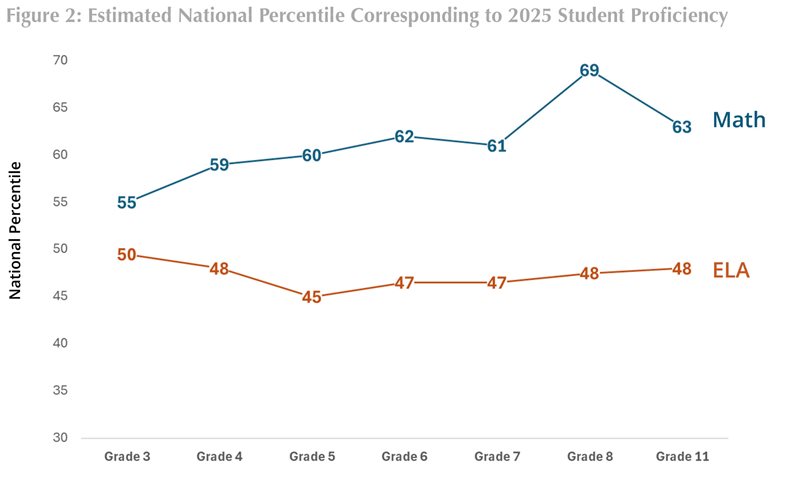

Figure 2 reveals that the new 2025 proficiency benchmarks have significant variation in rigor across grades and subjects, ranging from the 45th national percentile to the 69th national percentile. The variation in rigor across grades and subjects will manifest in the following state report card trends for most districts.

Most districts will see a steady drop in math proficiency from Grade 3 to Grade 8 that is unrelated to student, school, or district performance.

To be proficient, a Grade 3 student needs to score approximately at the 55th national percentile while a student in Grade 8 needs to score approximately at the 69th national percentile. This lack of alignment to national percentiles corresponds to a state-wide proficiency gap of 50% in Grade 3 to 33% in Grade 8.

A student who scores at the proficiency benchmark in Grade 3 will need to significantly outpace the nation in academic growth to remain proficient in Grade 8.

Most districts will show significantly higher proficiency in ELA compared to math.

It is easier for a student to be proficient in ELA than in math. As can be seen in Figure 2, the new math proficiency benchmarks are more competitive than the new ELA proficiency benchmarks. In Grade 6, the estimated national percentile for proficiency in math and ELA is the 62nd and 47th national percentile, respectively.

As seen in Figure 3, the largest proficiency gap of 24% exists in Grades 8 and 9.

Guidance for School Boards

The lack of articulation of the new proficiency benchmarks to state and national score distributions results in variation of proficiency rates at the local level that are unrelated to student, school, or district performance. As a result, ECRA offers the following guidance for Illinois school districts when interpreting and communicating proficiency rates using the new benchmarks. Caution is warranted:

-

Do not interpret percent proficient as the percentage of students at grade level. Proficiency benchmarks represent a long-term aspirational standard. While meaningful, proficiency does not consider what is typical across the state or nation. For example, for Grade 8 math, an individual student in Illinois could be deemed as not being proficient, despite the same student performing significantly above national averages.

-

Do not interpret increases in 2025 student proficiency compared to prior years as evidence of improvement. As explained in this article, increases in proficiency for 2025 compared to 2024 are likely due to state policy changes, not changes in underlying student achievement

Do not compare student proficiency between grades or subjects. Given the variation in rigor of proficiency benchmarks across grades and subjects, observed gaps in proficiency are likely due to differences in the underlying proficiency benchmarks, rather than differences in student achievement.

Solutions are recommended for Illinois school districts:

When interpreting or communicating proficiency, report a state or national percentile alongside the percent proficient metric for context. It is tempting to interpret raw proficiency rates as indicative of student or school performance. However, without the proper context via state or national percentiles, raw proficiency will likely be misinterpreted. Percentiles provide a simple and intuitive approach to understanding how your district’s student proficiency compares to other districts across the state or nation.

When evaluating or communicating district, school, or program performance, use student growth, not proficiency. Student growth is the most meaningful school improvement metric. Student growth is unaffected by issues related to proficiency benchmarks, and natively captures progress, providing a more evidence-based approach to evaluating performance. In addition, student growth accounts for unique challenges that local districts face by capturing performance relative to a baseline, as opposed to comparing all schools to the same proficiency standard.

Key Takeaway

The new proficiency benchmarks provide valuable insights, but without proper context, they may lead to misleading conclusions. When communicating student success, schools should frame proficiency rates in relation to state or national percentile ranks and emphasize student growth as the most valid measure of school improvement.